Today is a day for giving thanks... but we're not going to be doing that so much with these albums. I had a few things I wanted to say about them, but I don't want to waste too much of my time, so let's dispatch with them quickly.

Bloodbound - Field Of Swords

For most of these last twenty years, Bloodbound albums have been interesting only in how they were going to wind up disappointing me. I was disappointed when Urban Breed left, I was disappointed when Michael Bormann joined, I was disappointed when Urban left again, I was disappointed when the band tried on other band's sounds as if they were going to a costume party, and I was disappointed when they settled on a sound that is aggressively bland.

The band has been in a groove now for a few records, and that groove is worn rather thin. They remain professionals who put out a good sounding product, but Bloodbound is one of those bands that tests my patience when I say I want much that has heart and real humanity behind it. Everything about Bloodbound feels forced, written for the sake of putting out another album to keep their contract satisfied.

They have jumped on the bandwagon of writing about warn and history, which I don't find an interesting topic. Either there aren't enough words in a song to tell a meaningful historical narrative, or the words become stilted and dry trying to do so. And when your singer has a voice that has little personality to it, that leaves the whole thing feeling as if I've heard it a dozen times before. In fact, the only thing about this record that gets my attention at all is the fact their singer has two horns apparently implanted in his skull. I know it doesn't impact the music at all, but I find it hard to take the band seriously like that. Yes, they started out wearing corpse paint, but that is obviously an affectation. This is... more permanent, and a real head-scratcher why someone who plays the most inoffensive music would have that kind of image.

Bloodbound remains this; listen to "Tabula Rasa", forget the rest exist.

Spanish Love Songs - A Brief Intermission In The Flattening Of Time

I have said before that I don't give points for experimentation, because not all experiments work out. Sometimes, the desire to try something new leads a band down a path that doesn't fit their sound or style, and I don't think I should commend them for focusing on their weaknesses. You can experiment all you want, but releasing the results when they aren't up to par doesn't make you daring or brave, it means I'm going to question if you understand what makes your music appealing to the audience.

I asked that when Spanish Love Songs followed up the brilliant "Brave Faces Everyone" with a record that left behind all of the power and anger for a sound that was weaker, flimsier, and focused on the most annoying and aggravating vocal timbre. The record that helped get us through the hardest moments of the Covid era was replaced with a record that sounded like a bad version of 00s indie. I didn't understand the shift, and I have tried to forget it. But now there's a new EP, so that becomes hard to do.

Each of these songs comes with a collaboration, and the extra artistic voices are extra shades of gray in the band's new monotone. Rather than adding texture to the songs, they reveal how little of the core is left. The song with The Wonder Years should be a thundering expression of both band's raw passion, but instead the guitars noodle around a single synth note, while the main vocal drags along a chorus that sounds like a verse. The Wonder Years put out a wrestling theme song this year, and it buries this track so deep they'll never find the corpse.

"Cocaine & Lexapro" sounds like being passed out on drugs, your mind struggling to come out of its coma. "Heavenhead" wants to rock, but the amps are so small and undergained the guitars come off sounding like we're trying to listen to "Brave Faces Everyone" through Airbuds when they aren't in our ears. The reference to the flattening of time is apt, as this is a flat version of Spanish Love Songs; devoid of any power, passion, or damn memorable songs. I listened to this after "Brave Faces Everyone", and it's hard to believe we're talking about the same band. What a shame.

Thursday, November 27, 2025

Quick Reviews: Bloodbound & Spanish Love Songs

Monday, November 24, 2025

'No Thanks'-giving III

This is the season to give thanks for all the blessings life has bestowed upon us... but what's the fun in being happy all the time?

The last two years, I used this week as an opportunity to have a 'No Thanks'-giving, which was a Festivus-like twist on the holiday, using it as an occasion to vent about a few things in the world of music I wish I could say 'no thanks' to. They never disappear, but I can voice my displeasure nonetheless. The pool of complains is running lower now, but we still have a few things to talk about this year. Let's see what still gets my ire up.

Nostalgia Bands

Creativity is a fluid dynamic, I am well aware. It isn't easy to crank out new music on a regular basis, especially with the knowledge you need to keep doing it. Inspiration is nebulous, and sometimes it fades away from you. That has happened to me, and it's a different feeling than writer's block. Having no good ideas is a different reality than having no desire to keep creating. The former happens to us all, but the latter is more concerning.

We all know the bands out on tour who either haven't made a new album in decades, or don't play anything but the songs they recorded before CDs became a thing. They rake in huge money playing the same setlist of fifteen songs they have been playing for as long as our memories can stretch back. It's hard to blame them for doing it, but there is still something uncomfortable about artists who no longer strive to make art.

My former favorite band falls into this category. They still head out every summer and play shows, but this year marks fifteen since their last album, and we will soon be hitting five years since their only one-off single in all that time. At a certain point, it is less a question of whether they will ever make music again, and more a question of why we should care about them still existing as bands. If they are never going to give us anything new, and we have all heard them play the same songs a thousand times, what is exciting about them anymore?

Recently, Rush announced they returning to the stage, which is what put this particular thought in my head. Rush was one of the few bands that ever walked away with their head held high, saying a fitting goodbye to their fans, and ending with a well-received album to go out on. Now, they return a decade older, a decade further from being at their peak, and without Neal Peart. I would never expect them to make music without Neal (nor would I want them to), but something about them playing into the nostalgia of being Rush again, despite not being Rush anymore, leaves a sour taste in my mouth.

It's true in all facets of our culture; we can't leave the past in the past anymore. Between remakes, reboots, and stations that never stop playing the cultural touchstones of generations that came before us, we live in a world of nostalgia. People who never even lived through those times ape the sounds, styles, and looks, because they know that time better than their own. It's all... pushing some of us in the direction of thinking there isn't as much reason to keep looking forward anymore, when the future is merely going to be a newer version of the past.

Rock About Rock

As someone who has written lyrics for over half of my life, I have an affinity for the written word. There are two ways to write great lyrics, which can be separate or combined; write about something interesting, or say the mundane in an interesting way.

Unfortunately, when it comes to rock and metal, we wind up with far too many lyricists who act like a lot of the fans and treat the words as an afterthought. What that results in are countless rock and metal songs about how great rock and metal are, or how rock and/or metal the people singing the songs are. Ugh. There might not be a lyrical trope I hate more than writing music about the very music you're making. At least the pretend Satanists are very poorly trying to talk about an actual philosophical idea. Rock music is a boring topic for rock music.

And it all derives from one simple conceit; you shouldn't have to say it. Whether you are writing about how rocking you are, or how rocking your music is, the songs should speak for themselves. If you have to brag about your credentials, you probably don't have any to be bragging about. It's not unlike when you see someone driving either a hideously expensive sports car or a massively gigantic pickup truck, and you think to yourself how they are compensating for the flaccid effects of a lack of everything bravado stands in for.

This has plagued even the greats, as no less than Ronnie James Dio would often write "We Rock", or "Long Live Rock & Roll". You can't give yourself a nickname, and you can't gaslight people into thinking you rock more than you do. We laugh at people who constantly brag about the most mundane things for no other reason than they have to make themselves look good, but we allow rock and metal musicians to brag about being rock and/or metal as if any of it matters. Being metal to your core doesn't make you a good person, and it doesn't mean your music is going to be any good either. More time spent on making art, and less on how it is perceived, would be a big help.

Too Forgiving Fans

As fans, we are inclined to give people who make music we like the benefit of the doubt. That can be a positive character trait, but it can also expose our own weakness in not being able to set clear boundaries of what is and isn't acceptable. Of course, that could be the result of many people simply having no ethics to consider them violated, but I would like to think we can all agree that a few things cross the line.

Look at As I Lay Dying for all you need to know. Trying to contract a murder is a pretty clear red-line that should not be crossed, and while I'm not going to deny the possibility of rehabilitation, no one is forced to go into business with such people after they are held accountable. Not only did the band get back together, but the questionable person was accused of assaulting his wife (Don't ask me how anyone decided to be with him after knowing what he was capable of trying to kill his partners - I've stopped trying to understand people), which imploded the band again.

Far too often, there seem to be no consequences in this world anymore. People get away with the most heinous of things, because too many of us are caught up in the illusions of celebrity, and will forgive people if they entertain us in some way. If we look back, we can find countless examples of such things. How many of the classic rock stars of the halcyon days either wrote songs about pursuing underage girls, or actually did exactly that?

We know who these people are, but yet the stories become footnotes in their histories. They remain beloved by too many, and several of them are treated more as being our goofy uncles than being people who had predatory instincts. There are still members of the 'journalistic' sphere that trot these people out, and act confused and/or outraged themselves when some of us question why they buddy up with such people.

We should look back with degrees of horror that Ted Nugent wrote a song called "Jailbait" about being a low-rent Jeffery Epstein. We should be aghast that Winger was shouting "she's only seventeen" all over MTV in the past. We should be ashamed of ourselves that Metallica cutting their hair still gets more attention than the child exploitation that occurred on covers of Scorpions and Blind Faith albums.

I want to scream "Fuck you" at all the people who let this stuff slide without ever contemplating what this says about them. The only upside is that right now the 'band' Dogma is actually under some fire for the stories being told by former members that they were being mistreated and/or abused by the management who put this manufactured group together. They were being paid below minimum wage, barred by legal document from speaking as human beings, and one singer who turned them down couldn't get a clause put into her contract guaranteeing her physical safety. I'm encouraged to see some pushback, but it still isn't enough. There hasn't been any word from Dogma's label or distributor holding them accountable, or dropping them as clients. I fear when the next desperate musicians sign up, and a new single/video is released, we're going to forget all about this.

When I say I'm glad I don't call myself a 'metalhead', or part of any music culture, this is why. Too many people can live with themselves supporting evil, but I can't.

Thursday, November 20, 2025

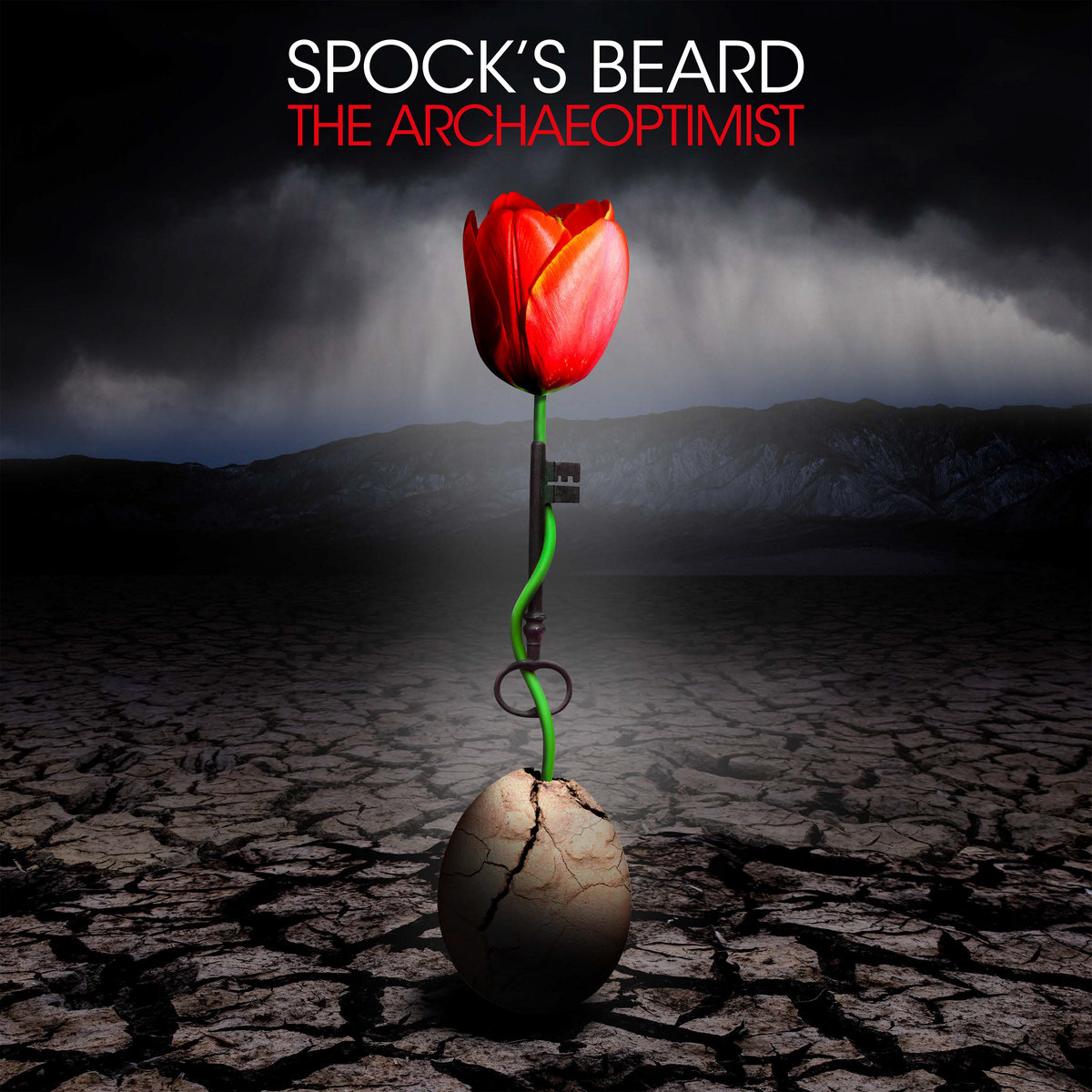

Album Review: Spock's Beard - The Archaeoptimist

When your band was named as a joke about a ridiculous episode of a sci-fi show, a thirty year career is probably not what anyone had in the cards. And yet, despite their name being a reference to the evil version of Spock (I would have gone with Garth Knight on "Knight Rider", myself), they continue on into their third decade of neo-prog.

There have been up and downs along the way, with the transition from Neal Morse to Nick D'Virgilio forcing the band to completely reinvent themselves. They did that, only to find themselves shifting yet again when Ted Leonard took over for the third chapter of their career. This album might be the biggest shift of them all, as we find the creative engine being provided by keyboardist Ryo Okumoto, which is in essence the only difference between this and the now several albums the rest of the band has put out as Pattern Seeking Animals.

So without any of the key songwriters from their career doing the heavy lifting, does Spock's Beard have anything worth saying... or worth listening to?

"Invisible" doesn't do much to answer that question as it starts the record, going through the motions of prog riffs while offering very little in the way of the band's trademark melodies. Neal was expert at injecting pop fun into their sound, and Nick had a slick charm, but this song sounds more like one written by someone who has never been a singer, nor worked with one. Ted is given very little to do, and what he does sing has little appeal or hook. A band that was able to transcend the cliches of prog is now slipping right into them.

"Afourthoughts" adds a new chapter to the band's "Thoughts" series, which is a nod to the past, but also a tether. Yes, it shows that Spock's Beard is still Spock's Beard, but having a song that borrows so much influence from their own history can also come across as the band running low on inspiration. It's a fine line, and I'm not sure which side I currently fall on. Perhaps if the song was a touch sharper I would be more generous to the concept.

The meat of the album comes at the end, with the twenty minute title track followed by another ten minute song. These journeys are what prog fans love, but they also give an easy 'out' to the band in not having to write compelling songs. Too often, fans will accept anything that is long, thinking that somehow writing a longer song must be harder, or that length indicates quality. 'Size doesn't matter' is a real saying, they should learn.

The longer tracks, because they demand so much of our attention, are where Spock's Beard shows the shortcomings of this incarnation. Neal has made a career out of writing epics constructed from masterful pop tunes stitched together, and Nick's era had a few that were able to keep momentum going. These songs, though, struggle to maintain either flow or energy. Much of "The Archaeoptimist" is instrumental, and the various riffs and solos are not the kind of playing that is likely to lodge in your mind. Couple that with the vocal sections that are flat, and you get a song that is twenty minutes of trying patience. The only bit of interest was trying to figure out which 80s pop song the second vocal section feels like it's ripping off. I'm not sure I figured that one out.

Ultimately, this album reminds me of the story of Credence Clearwater Revival. In that band, John Fogerty wrote all their songs, and they were hugely successful. Eventually, the rest of the band wanted to prove they were just as capable. That led to an album considered one of the great disasters of classic rock, and the end of the band. This isn't that bad, but it does serve to remind us that great songwriters are rare. It's amazing Spock's Beard was able to survive losing Neal Morse's writing, but now that they don't even have John Boegehold providing songs, the fact is that the rest of the band doesn't have the same killer instinct for writing great songs.

Whether it's this album, or Pattern Seeking Animals, the entire Spock's Beard sound has gotten as played out as... well... the idea of a stupid beard indicating a character is evil.

Monday, November 17, 2025

What Is A Song?

At a fundamental level, a song is nothing more than a collection of musical ideas, but we know it's more than that. There's something magical about a great song that extends beyond chord progressions or notes on staff paper. We can study theory our entire lives and not be able to use it to explain why songs move us the way they do. There is something ethereal about songs, something only a few people have ever been able to be able to tap into again and again.

Songs are music, so it would seem like people who write music are writing songs. But is that really the case? When we look at any number of rock and/or metal bands, we see a fairly common structure where an instrumentalist will write and compile the riffs, while the singer will then write the lyrics and melody to sit atop. That leaves us to question if they are both writing the song, if only one of them is doing the heavy lifting, or if it all depends on the nature of the song when it is finished.

I once got in trouble for arguing that a guitar player in a major band wasn't necessarily a 'songwriter', because it could be said he was just compiling riffs. This was not said about Metallica, although the assembly-line nature of their riff collages is now very well known, and does give some credence to my line of thinking. No, what I was getting at is a fundamental truth about songs that rock and metal fans don't like to admit to themselves, because it works against the nature of the music we listen to.

Songs are defined by their melodies.

In the majority of cases, that is the truth. The vocal and the vocal melody are the identity of the song that the casual audience will know, in most instances. While there will always be songs like "Iron Man" known for a riff, or "We Will Rock You" where the drum beat (despite its simplicity) sets the tone, the majority of songs exist as the vocal, if for no other reason than that is the human connection we have with music. It's far easier for the listener to sing along with a song than it is to hum a bass-line.

But this extends further. If you look online, you can find covers of nearly any song in the world being done in different styles. If you take a pop song and give it heavy guitars and double-bass drumming, it will still sound like the same song. If you take a metal song and play it on piano, it will still sound like the same song. You can change nearly everything about the instrumental, and the song will still be identifiable as the same composition, so long as the main melody remains the same.

Think about the inverse. If you take most of your favorite songs and put a different lyric and vocal melody on them, would you consider them to be the same song? That was inadvertently the case when Beyonce and Kelly Clarkson were essentially given the same backing track. The results were "Halo" and "Already Gone", two songs that sounded similar, yes, but they were hardly the same. That's for the simple reason that we only have so many notes, and it's the inflection of the human voice as we put words to those notes that gives songs their unique identity. You can almost always identify what song a singer at karaoke is performing, no matter how bad they might be.

That isn't to say guitar players and the like aren't important, but it does go to the question of why singers are so often viewed as being the face of a band. They are the one piece of the song that cannot be removed. You can perform songs acapella and they work. You can't perform most songs without the singer and have them hold up. That simply isn't the format our popular music is written in. And given how infrequently a purely instrumental song becomes popular, that feels like a more universal truth than merely a happenstance of how the system has been set up.

That isn't to say instrumentalists aren't important, or that you can't prefer guitar riffs to vocal lines if that's your thing. I'm merely musing on the nature of what we listen to, and how sometimes our communities get siloed off to such a degree we lose touch with the wider picture. We are the types who keep making lists of the greatest guitarists based primarily on their ability to solo, when the fact of the matter is that not only are solos only a fraction of playing a song, but guitar itself is usually not the prime factor in making a song what it is. Listen to any sports arena chanting the riff to "Seven Nation Army" and tell me how many guitar players have ever played a solo that has moved so many people.

The magic of music isn't in dexterity and amazing people with flashy skills, it's in writing and playing songs that stick with us for our entire lives. Those are the songs that mean everything, the ones that will live forever. It's worth taking a moment to really think about what we're remembering, and why we're remembering it.

Thursday, November 13, 2025

Singles Roundup: Jimmy Eat World, Foo Fighters, Soen, & Michael Monroe

The year is winding down, but new songs never stop. Do they point us toward a good start for next year? Let's find out.

Jimmy Eat World - Failure

You could count on a Jimmy Eat World album every three years. Some were life-changing, and some were just enjoyably good, but the band was delivering on a consistent basis. Their last three-year cycle was missed, and now we're at the tail end of the next. It has been six years since their last album, and that leaves me worried not if they will ever make another full-length, but what it will be if they do. They have put out a handful of singles in the intervening years, but they are not the magic I have come to expect.

This latest effort does not change course, giving us just two minutes of slow fuzz that fails to deliver any of the band's power, emotion, or memorable hooks. It floats along, but never seems to go anywhere. It drones without building to a new idea. It sounds like the demo b-side to one of their lesser albums. I don't know if the creative muscles aren't as strong when the cycle gets broken, but the fact this song reminds me more of Weezer's worst attempts to recapture their formative sound than it does Jimmy Eat World being themselves is not a positive sign.

Foo Fighters - Asking For A Friend

The band's last album found them using tragedy to reconnect with their early sound. they were going back in time to try to process what the future was going to be, which this single says might be a continuation of Foo Fighters just trying to be Foo Fighters again. That wouldn't be a bad thing at all, given how weak a couple of the albums were in that run where they felt they needed a gimmick for every release.

This song is the closest the band has come to sounding like "One By One" since that album, which is interesting to me, because I've rarely heard them talk positively about that album. It might be my favorite of theirs, but for the most part it isn't considered a highlight. That is the core sound of this song, though, with a big fuzzy riff, Dave digging into his gritty scream, and a sense of droning that hasn't been present in their music for many years. I find it rather fascinating to hear them back in this place, and it sounds more natural than when they were attempting to be an adult-contemporary band. Perhaps the setback and the pain have reoriented their artistic sights.

Soen - Mercenary

The new year will be kicked off with a new Soen album, which just feels right. This is the second single, and it has me thinking about Motorhead, of all bands. Soen's last four albums have come in #1, #1, #1, and #2 on my year-end lists, but I'm now wondering if we have started our descent from the heights.

This song, and the previous single, point to a continuation of the last two albums. I love those records, but a third in a row that sounds nearly identical might be taking things a bit too far. There is having a core sound, and then there is being a one-trick pony. "Lykaia", "Lotus", and "Memorial" all sound similar, but different enough to give us new facets to the band's sound. Now, this sounds like three albums in a row that will be indistinguishable from one another. And as much as I do love Soen, that could be one too many.

The chugging rhythm of this song is familiar. The solo break is expected. The vocal is solid, but exactly what I would expect. I'm not saying Soen needs to reinvent themselves, but when it becomes hard to tell one album from the next, even if the only difference is a production choice, getting excited for more music takes more effort on my part. I fear that's where Soen is now heading.

Michael Monroe - Rocking Horse

"Blackout States" caught me off-guard and floored me. I have liked the two albums that followed, but each one a bit less than the previous. I don't know if it's me, or the albums themselves, but the magic hasn't felt nearly as strong as it used to. The next album is due to come in February, and this first single is giving me yet more reason to worry that the illusion has been spoiled, and smoke and mirror are all that is left.

In these brief two minutes, the song delivers the right attitude, but without the right soul. The riffs have none of the sleazy charm or groove as his best work, and Monroe's vocals aren't given a solid melody either. I loved "Blackout States" for the huge sing-alongs that came with the dirty sound, and that is completely absent from this track. Perhaps it will be an outlier, as I wasn't the biggest fan of "One Man Gang" when it released either, but when such a weak song is chosen as the best to present to the audience to get their attention, I'm concerned.

Monday, November 10, 2025

A "Warning" On Time, Aging, & Remastering

That's an interesting question, as we have countless examples of people trying to update and improve art, and it creates a paradox not unlike the Ship Of Theseus. When we reach back in time to alter the art we have lived with for however long, it no longer is that piece of art, and yet we still know exactly what it is. Identity is not a simple concept when you break it down, and that follows through to art as much as anything else.

Is "The Last Supper" still the painting put on the wall by Leonardo when it's estimated only 20% of his original brush strokes still remain?

I will not profess to have even a sliver of the insight necessary to answer that loaded question, but I can carry the thought over to the world of music. We know that the recordings aren't the same when a band goes into the studio and records a new version for reasons that usually have to do with rights and money. The composition is the same, and the production might be attempting to be exactly the same, but performances never are. They are the same song, but not the same 'song', if you know what I'm trying to say.

Things get more complicated when we talk about more subtle changes, such as the remastering of albums that comes along very often at milestone anniversaries. The artists want to give their work a fresh coat of paint, ostensibly to make them sound better than ever, but realistically to make them sound acceptable to a younger audience that has yet to buy their own copies. The producers turn a few knobs, alter the frequency spectrum, and usually compress the audio even further, and we wind up with a record that is the same as the one we have always known and loved, but yet it isn't.

So I revert to my initial question; when does changing a piece of art get to the point it is not longer the same as we have known it?

This came to mind recently as Green Day is releasing a twenty-fifth anniversary edition of "Warning". I've already written about the album itself for its anniversary, so I want to instead focus on the recording itself. In addition to demos and live material, the new set comes with a remaster of the album to update it for today's tastes. That is rather interesting to me, not for any changes they could make, but for how unnecessary the process appears to be.

I still play "Warning" regularly, and every time I do it strikes me just how great the album still sounds. "Warning" was released in that stretch of time when expensive studio gloss was still paid for, and the loudness war had yet to set in. There is a depth, clarity, and richness to the sound that is expansive in a way today's rock records rarely are able to achieve. Green Day sounded like a band with a major label budget to work with.

So why would they remaster an album that sounds great?

There are two main answers; 1) Today's listeners want/expect albums to be uniformly louder and compressed, and 2) They have to have some hook to justify charging us more for a new version of an old product.

Neither is a great defense, but the business aspect is an aside from the artistic one. We have yet to ask whether or not this new version of "Warning" sounds better, or even as good, as the original. That, above all else, should be the most important facet of this conversation.

The fact of the matter is that the remaster does not sound as good as the original. That depth and clarity is flattened out, with the overall sound coming across thinner and more brittle. Instead of sounding more powerful for packing a harder punch, it sounds more fragile and closer to the breaking point. There is a paradox in music where if guitar amps get cranked too hard, they stop sounding heavy and become a soft mash of fuzz. The same happens when productions are pushed to be too loud and compressed, as it leads to recordings that feel forced.

This phenomenon has become a plague upon us. If we are lucky, they are simple remasters that highlight bits that might have been better off keeping to the background. In more extreme cases, full remixes are done that change the entire character of albums. Dio's "Holy Diver" was remixed for its fortieth anniversary, and listening to that is like hearing someone taking a chisel to "David" because they wanted to give him more girth 'down there'. The result was a record that lived its entire duration in the 'uncanny valley', because it was clearly still "Holy Diver", but it was different enough all the way through that I could never get comfortable thinking about it as anything but a costume worn by the original. Elvis Costello did the same thing to "This Year's Model", transposing the keyboards for guitars as the main instrument, which completely destroyed the very sound that defined the album.

So are these albums still the albums we started out with? Philosophy would tell us, as in the paradox, there is no easy answer to the question. It is a matter of degrees, and emotion. Remasters that sound enough like the original without being offensive can still be the same album, just seen through a different pane of aging glass. Remixes don't feel the same at all, and make us question our very memories of the music. It's harder to say going back in and making fundamental changes leaves us with the same piece of art.

As in the case of "The Last Supper", we have a contemporary copy to see what it was supposed to be, and we can catalog the differences. But in that case, no one alive has ever seen the original intention on that wall, so the restoration is the only knowledge we have of the painting. For these albums, we still have the originals, and many of us still have our memories. Those can't be brushed away like the layers of dust and grime.

We need to be careful when we touch history. Our ears change and fail us as we get older, so all of this search for improvement is trying to balance reality to fit our more limited senses. It's a compensation for what we can no longer hear, and a twisting of the truth that allows us to believe we aren't getting older.

I'll keep my memories, thank you very much.

Thursday, November 6, 2025

Album Review: Creeper - Sanguivore II: Mistress Of Death

Creeper is a musical version of that quote. Over their first three albums, they tried on different guises, exploring sounds that had little connective tissue between them. Their debut was a nearly perfect emo/pop-punk record that hit right as the new wave of that music was cresting. Their second album 'borrowed' from classic rock, with songs that very obviously cribbed bits from both Meat Loaf and Bruce Springsteen (on the accompanying EP). Album number three went full Goth, revealing the difference between being slightly gothic and being full-on Goth. There is overkill, and Creeper ended up covered head to toe in blood.

The problem with all of this is that after three full records, I can't tell you who Creeper are. There is a sense of drama in common, but otherwise Creeper are a group of theater kids running through sketches one after the other, with no framing device to explain. Sketch comedy is a viable artform, but it doesn't provide insight into the performers the way other formats can. Likewise, Creeper have tried on costumes, but have shown us next to nothing of who is wearing them.

Album number four is different, in that they are not making drastic changes. This record is a direct sequel to their Goth album, which is a daunting reality, as that one was easily the worst of their play-acting trilogy.

Creeper plays right into my hands with the opening spoken word piece, but in a way that also makes their penchant for 'homage' too obvious to not feel a bit like identity theft. The narrator sets the stage for vampiric fun, but in the course of doing so uses the phrase that sometimes "going all the way is just the start". That, for the uninitiated, is a line from a Jim Steinman song that is only known to the hardcore. While the reference is nice, it feeds into the feeling I've always gotten from Creeper that they're more interested in amusing themselves with 'borrowed' in-jokes than in making honest music of their own.

The good side to this album is that for a while these concerns can be put away. The early singles "Blood Magic (It's a Ritual)" and "Headstones" are both more fun than anything Creeper accomplished on the first chapter of this story. Those songs are campy as all hell, especially when the title to the latter is delivered as an oral sex allegory, and too damn catchy for their own good. That is what Creeper needs to lean into, because if they are going to write about campy subjects, they need to do it with tongues fully in cheek. Which set of cheeks is up to them, as both can work.

As soon as that sense of fun dissipates, the album bogs down, and bogs down hard. "Prey For The Night" is the same mediocre goth tones as the last album, while "Daydreaming In The Dark" is rock only in name. The chorus is so billowy and soft it's hard to keep my attention focused long enough to try to figure out what the backing vocals are trying to say through the rather blurred performance. Reading the title, I thought it was going to borrow from Springsteen's "Dancing In The Dark" in the same way they used "Because The Night" to make their own "Midnight", but alas, that was not the case. For as much as we sometimes rag on Springsteen around here, he at least knows how to use his genre experiments to explore different sides of his personality.

"Razor Wire" is sung by Hannah, which is a refreshing change from Will's deep goth affectation, and comes with a jazzy cabaret feeling. It doesn't mesh at all with the rest of the album, especially with the sax solo that might be the best thing about the entire record, and it continues to evoke questions about exactly what Creeper is trying to do. One moment they want to have stupid fun with sex puns, the next minute they want to be scary vampires. One moment they're playing energetic rock, the next minute they're dragging along as if the batteries on an old AM radio are beginning to fade and die.

It would be too on-the-nose to say Creeper is dead to me, but they are reaching the point where I don't see the point in continuing to give them chances to disappoint me. Now, it feels like every good song they write is either a fluke, or a deliberate troll to trick me into listening to their 'artistic' drudgery. There's a rhetorical question about what the sound of one hand clapping is, and I think we can twist that in a more Creeper-ish direction; which is the dominant feeling if one is flexible enough to suck their own dick?

That question is more interesting to ponder than this album is. Please, please, please let this be the end of this phase for Creeper. I can't take any more of this shit.

Monday, November 3, 2025

Revisiting AI Music: Theory Put Into Practice

We would think AI music should fall into that category. As I said, there is absolutely something slightly disturbing about the thought that music is being created and fed to us through algorithms rather than inspiration. I completely understand the antipathy, and then...

I began experimenting with the AI behind some of this music. I have mentioned my own experience as a failed musician countless times over the years, because that colors everything I think and say about music. Creating for myself gives me insight into the process, but more importantly it gives me an over-arching philosophy of what the art is that perhaps most listeners have never given any thought to. You can't be merely a 'casual listener' if you are neck-deep in the process yourself.

Curious, I opened the AI program, and I plugged in a set of lyrics that had never amounted to anything. After typing in a few quick prompts, I pressed the button and waited while the spinning wheel told me the algorithm was hard at work turning my words into a song. I doubted it could find 'my voice', so to speak, as every human singer I have shown my work to has told me my cadences and metaphors are unique to me... and perhaps a bit difficult for anyone else to wrap their heads around. My wiring is unusual... color me surprised...

When the wheel stopped, and the play button appeared, I was expecting to laugh at the results. I listened, and the vocal was indeed plastic and artificial, but the song itself wasn't. The 'composition' I was listening to hit the right marks, found the right atmosphere, and delivered a melody that was immediately familiar, yet sharper and catchier than anything I had tried and failed to sing for myself. I was intrigued.

The experiment continued, and I transformed more and more lyrics. Quickly, I was amassing a set of songs that sounded objectively bad, but were doing for me what I could never do for myself. After all my favorites were turned into the singer/songwriter material I had always imagined, I started experimenting with my more emo side, and even more lyrics got turned into heavier songs that fed a side of my personality that was always dormant in the background. I could not in good conscience tell anyone it was great music, but in the back of my head the thought was developing.

As luck would have it, only a few days after I finished my experiment, the program released a new and improved modeler. I put one of the songs it gave me back into the algorithm, and waited to see how dramatic the difference from one week to the next could be. I would not have believed the result could be a quantum leap forward, and yet that's exactly what it was. The same song that was promising but robotic became all too human. The sound expanded, the details bursting forth, and the vocal now sounding almost perfect. I was floored that I was listening to 'my' song, not only played better than I could, but sung better than any of the demos I had received over these last two-plus years from real singers.

I kept on, running all of the songs through the new model, and when I was done I had two full albums of songs that I was struggling to wrap my head around. They were my songs, and many of them borrowed the contours I sang the language with, but they were more than I had ever dreamed of. My imagination is not vivid, and my hopes were always small enough to fit into a card slot in my wallet. This, while not 'real' in the sense of the word, was more real than anything I heard echoing in my daydreams.

That brings us to the crux of today's discussion, which is to address what this means for music going forward. My experiences have told me all along that there are countless people out there with great ideas, and with the drive to make great art, but who lack the requisite talents or connections to make it happen. The human limitations keep us from reaching the intellectual potential we have, and AI is helping to democratize talent, in a way. I have skill as a lyricist, but no facility as a singer, so AI is able to step in and give me a voice my body cannot. Is that so different than bands bringing in studio musicians to play the parts they could not master for themselves? Maybe not.

But what this really means is our relationship with music might need an adjustment. Our love of particular artists, and our obsessions with them, will not come necessarily from their ability to twist notes into fascinating riffs and melodies, but in the way they connect to us on a human level. To once again reference Taylor Swift; the reason she is the biggest artist in the world right now is not that she writes the best pop songs (that's a debate), but because her persona and lyrics speak to people in a way they relate to.

THAT is what music is going to become. AI is a useful tool in helping us to flesh out our ideas, but it is the ideas themselves that will only grow more important as this proliferates. A lyric that speaks to people's lives will elevate a song more than a vocal that is perfectly in tune every nanosecond of a performance. Writers with something to say, something important to say, will still stand out from the crowd of basic language every algorithm will piece together from raw syntax.

So... do I love the songs AI helped me create because they are great songs, or because they are my songs that express some of my deepest thoughts?

Both might be true, but it is the latter that makes them important. Catchy songs are great, and they're fun, but so many of them exist already that more of them aren't going to stay with us. Songs that mean something to us will, and what's the harm in AI helping people with something to say be able to have their message reach us?

Speaking from experience, it can be the difference between pride and depression, between feeling like you've accomplished something and wanting to give up on everything. I'm not in a rush to take that away from anyone, myself included.